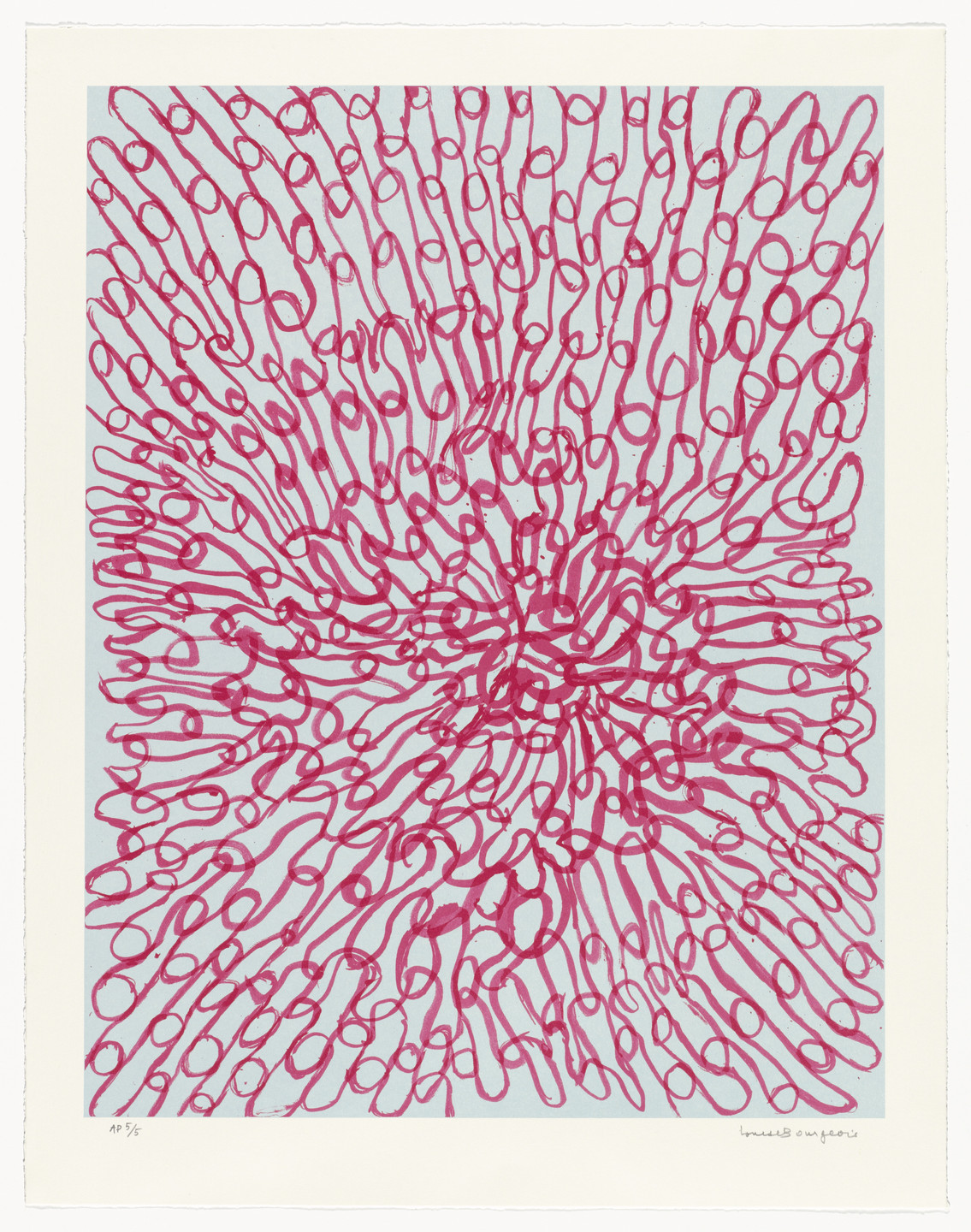

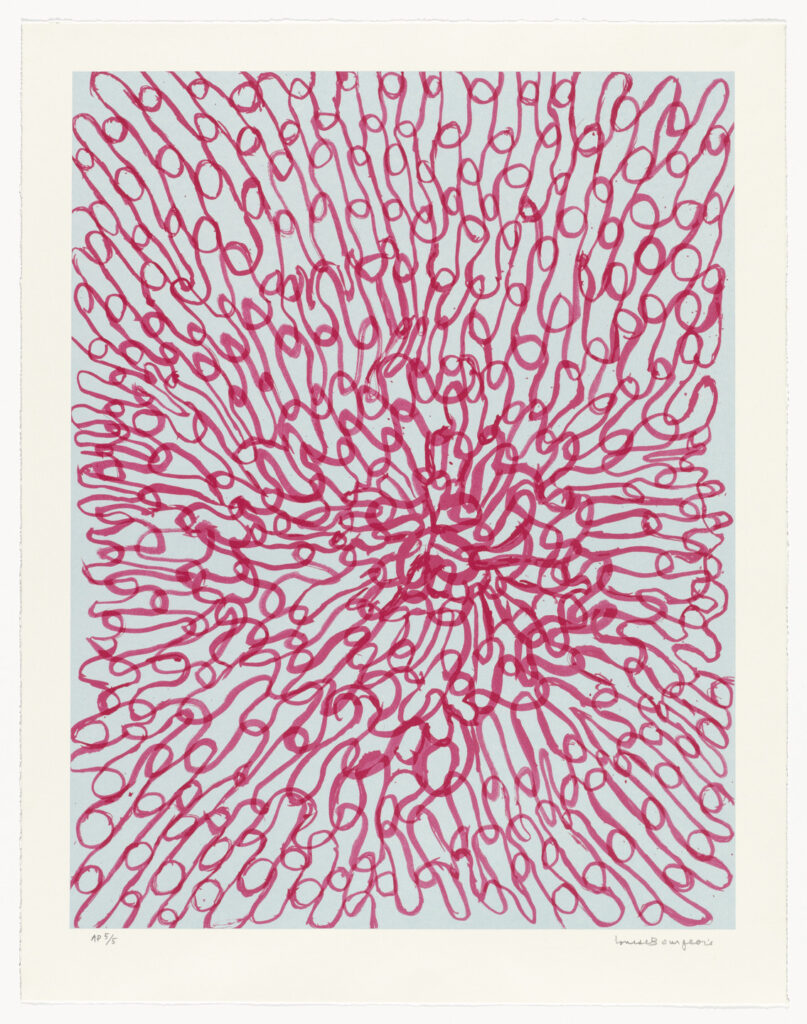

Louise Bourgeois, Insomnia, 1996. Ink on paper. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Architecture of Insomnia

Words CLAIRE

On designing ourselves into sleeplessness.

The private bedroom is barely two hundred years old. For most of human history, sleep happened in shared spaces—bodies pressed together against cold, livestock nearby, darkness total and unquestioned. We slept this way not by choice but by necessity, and our biology adapted to those constraints: the cold air, the absolute dark, the absence of anything to do but rest.

Then we invented privacy. And light. And climate control. We built rooms designed solely for sleep, then systematically filled them with everything that prevents it.

I.

Medieval households collapsed into one or two rooms at nightfall. Lords claimed beds while servants took floors, but even wealth rarely bought solitude. The room was cold—genuinely cold, the kind that forces you under heavy covers and drops your core temperature whether you want it to or not. There were no candles burning through the night; tallow and wax cost too much. Darkness was complete.

The body knew what to do with these conditions. Core temperature fell, melatonin flooded the system, sleep arrived. Not because medieval people were better at rest, but because their environment demanded it.

By the 18th century, emerging wealth created new spatial possibilities. Families began partitioning homes into separate chambers. The Victorians made this a moral imperative—private bedrooms as bulwarks against impropriety, physical distance as spiritual protection. But even as the bedroom became individualized, it remained austere. A bed, a dresser, windows without treatment. The room stayed cold and dark because heating and lighting entire homes remained expensive and impractical.

II.

Edison’s bulb arrived in 1879. Electrification crept through cities over the next fifty years, and with it came the gradual untethering of sleep from solar rhythm. Bedtime became negotiable. You could read past sunset, work into evening, extend social hours indefinitely. The bedroom’s enforced darkness—the thing that had always signaled the body toward rest—dissolved into optional dimness.

Central heating followed in the postwar housing boom. By the 1960s, most American homes maintained a constant 68 to 72 degrees year-round. We eliminated the discomfort of cold bedrooms, not realizing we were also eliminating a biological requirement. The body needs to shed heat to initiate sleep. Ideal sleeping temperature hovers between 60 and 67 degrees—cool enough to feel slightly uncomfortable uncovered, which is precisely why it works. We solved for comfort and engineered away the condition that produces rest.

III.

The television entered American bedrooms in the 1960s as furniture, a status object that happened to emit light and sound. Within a decade it became infrastructure—the thing you left on for company, for noise, for the illusion of not being alone. The bedroom was no longer exclusively a sleeping chamber. It was also a theater, a companion, a door to elsewhere.

But television at least had an off switch, a discrete endpoint. The smartphone has no such boundary. It charges on the nightstand like a pilot light, screen facing up, pulsing with notifications. We reach for it before sleep, conditioning the last conscious moments with cortisol and blue light. We reach for it immediately upon waking, often before our eyes have fully opened. The bedroom now contains email, news, social comparison, work emergencies, political rage, infinite scroll. Everything except the signal to rest.

Blue wavelength light suppresses melatonin at the exact hour the body needs it most. Even minimal exposure—a charging indicator, an alarm clock display—registers as false dawn, telling the brain to delay sleep. We know this. The research is decades old, replicated across populations, unambiguous in its findings. Yet ninety percent of Americans use screens within an hour of attempting sleep, performing a nightly ritual of self-sabotage so normalized we barely register it as choice.

IV.

The pandemic collapsed whatever boundaries remained. Millions of people suddenly worked from bed, ate lunch where they’d later try to sleep, attended Zoom calls from beneath covers. The bedroom absorbed every function it was meant to exclude: productivity, stress, decision-making, social performance. A space that once signaled rest now signals everything—and therefore nothing.

Sleep researchers have a term for this: stimulus control. The principle is simple. The bed should mean only sleep. Not work, not entertainment, not worry. Train the brain to associate the space with a single state, and that state becomes easier to access. It works in clinical settings. It fails in nine hundred square-foot apartments where the bedroom is also the office, the dining room, the only place to take a private phone call.

We treat this as a personal failure—my insomnia, my inability to disconnect. But it’s a design problem. We built homes that make stimulus control impossible, then pathologize people who can’t sleep in them.

V.

Meanwhile, we’ve spent billions engineering better beds. Adjustable bases, memory foam that contours to your body, cooling gel, embedded sensors that track movement and heart rate and recommend optimal sleeping positions. The mattress industry frames sleep as a problem of insufficient technology, one more optimization away from solution.

But the bed is the least important variable. A modest mattress in a cool, dark, unstimulating room will always outperform a six-thousand-dollar smart bed in a 72-degree chamber glowing with screens. We’ve optimized the wrong thing, solving for comfort while ignoring conditions.

Those old cold rooms got darkness by default—no streetlights, no devices, no light pollution bleeding through uncurtained windows. They got cool air because heating was expensive. They got boredom because there was nothing else to do. These weren’t features; they were constraints. But constraints can be generative. They forced the body into the only available state: rest.

VI.

Americans now average seven hours of attempted sleep per night, down from nine a century ago. One in three adults reports chronic insomnia. We reach for pharmaceutical solutions—melatonin, Ambien, Benadryl, magnesium, CBD. We buy blackout curtains and white noise machines and weighted blankets, building makeshift sensory deprivation within rooms designed to stimulate. We download apps that track our sleep and tell us we’re doing it wrong, adding data anxiety to the list of things keeping us awake.

We rarely ask whether the room itself is the problem.

The bedroom’s evolution maps our priorities with uncomfortable precision. We chose light over darkness because we could. We chose warmth over cold because discomfort felt like failure. We chose connection over isolation because screens promised us the world. At every juncture, we optimized for immediate comfort and convenience, dismantling the environmental conditions that facilitate sleep.

We didn’t do this maliciously. We did it incrementally, one small improvement at a time, each change defensible on its own terms. Of course you want to read in bed. Of course you want to be warm. Of course you want to check if anything urgent happened overnight. Each decision made sense individually. Cumulatively, they built rooms where sleep becomes increasingly difficult, then impossible, then medicalized.

The crisis isn’t biological. It’s architectural. We designed ourselves into insomnia, one comfort at a time.

Visual Note: We chose Louise Bourgeois’s Insomnia (1996) because it doesn’t illustrate sleeplessness—it enacts it. The loops radiate outward in pink ink, tangled and compulsive, creating density without resolution. It’s the visual equivalent of lying awake: thoughts that won’t organize, energy that won’t discharge, the mind circling the same territory for hours without arriving anywhere. Bourgeois made this during a period of chronic insomnia, describing the repetitive marks as self-soothing. But the image itself isn’t soothing. It vibrates, refusing stillness even as it documents the desperate desire for it.

Words CLAIRE